As the sea ice shrinks in the Arctic, the plankton community that produces food for the entire marine food chain is changing. New research shows that a potentially toxic species of plankton algae that lives both by doing photosynthesis and absorbing food may become an important player in the Arctic Ocean as the future sea ice becomes thinner and thinner.

Microscopic plankton algae, invisible to the naked eye, are the foundation of the marine food web, feeding all the ocean´s living creatures from small crustaceans to large whales. Plankton algae need light and nutrients to produce food by photosynthesis.

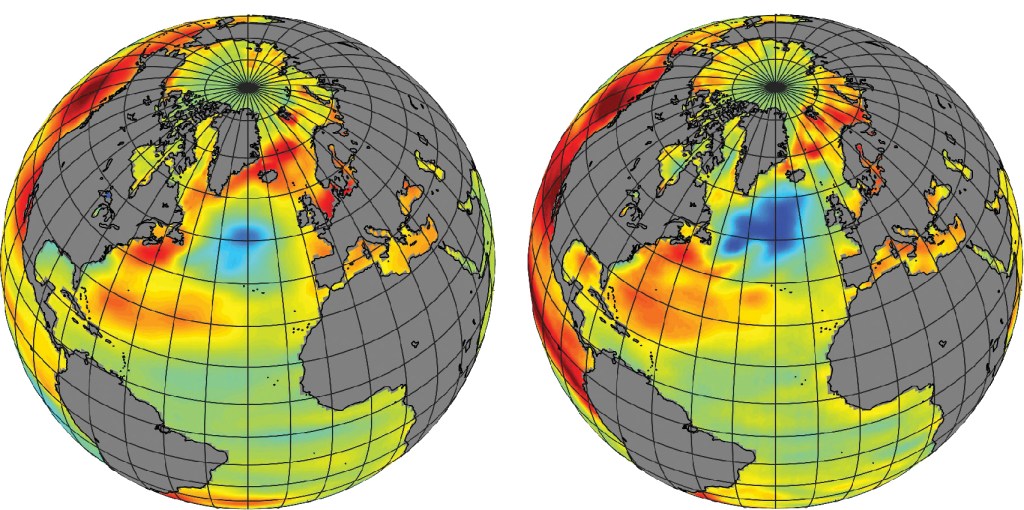

A thick layer of sea ice – sometimes covered with snow – can reduce how much sunlight penetrates into the water and stop the algae getting enough light. However, as the sea ice is becoming thinner and less widespread in the Arctic, more and more light is penetrating into the sea. Does this mean more plankton algae and thus more food for more fish, whales and seabirds in the Arctic? The story is not so simple.

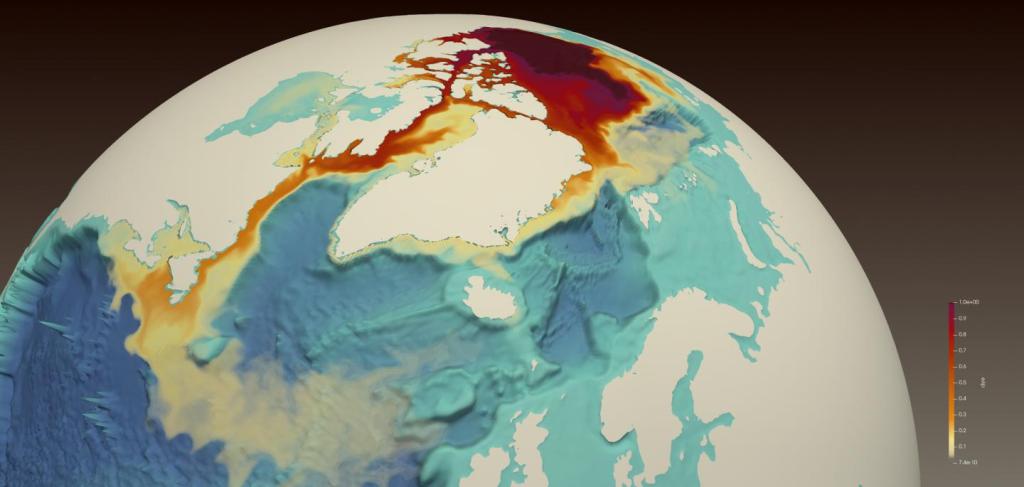

More light in the sea will only lead to a higher production of plankton algae if they also have enough nutrients – and this is often not the case. With the recent increase in freshwater melt from Arctic glaciers and the general freshening of the Arctic Ocean, more and more fresh and nutrient-depleted water is running out into the fjords and further out into the sea. The fresher water lies on top of the more salty ocean and stops nutrients from the deeper layers from mixing up towards the surface where there is light. And it is only here that plankton algae can be active.

Mixotrophic algae play on several strings

However, a new study published in the journal Nature – Scientific Reports shows that so-called mixotrophic plankton algae may play a crucial role in the production of food in the Arctic Sea.

Mixotrophic algae are small, single-celled plankton algae that can perform photosynthesis but also obtain energy by eating other algae and bacteria. This allows them to stay alive and grow even when their photosynthesis does not have enough light and nutrients in the water.

In northeast Greenland, a team of researchers measured the production of plankton algae under the sea ice in the high-Arctic fjord Young Sound, located near Daneborg.

“We showed that the plankton algae under the sea ice actually produced up to half of the total annual plankton production in the fjord,” says Dorte H. Søgaard from the Greenland Climate Research Centre, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and the Arctic Research Centre, Aarhus University, who headed the study.

“Mixotrophic plankton algae have the advantage that they can sustain themselves by eating other algae and bacteria as a supplement to photosynthesis when there isn’t enough light. This means that they are ready to perform photosynthesis even when very little light penetrates into the sea. In addition, many mixotrophic algae can live in relatively fresh water and at very low concentrations of nutrients – conditions that often prevail in the water layers under the sea ice in the spring when the ice melts,” Dorte H. Søgaard explains.

Toxic algae kill fish

For nine days, the researchers measured an algal bloom driven by mixotrophic algae occurring under the thick but melting sea ice in Young Sound during the Arctic spring in July, as the sun gained more power and more melt ponds spread across the sea ice, gradually letting through more light.

The algae belong to a group called haptophytes. Many of these algae are toxic, and in this study they bloomed in quantities similar to those previously observed in the Skagerrak near southern Norway. Here, the toxic plankton algae killed large amounts of salmon in Norwegian fish farms.

“We know that haptophytes often appear in areas with low salinity – as seen in the Baltic Sea, for example. It is therefore very probable that these mixotrophic-driven algae blooms will appear more frequently in a more freshwater-influenced future Arctic Ocean and that this shift in dominant algae to a mixotrophic algae species might have a large ecological and socio-economic impact.” says Dorte H. Søgaard.

The researchers behind the project point out that it is the first time that a bloom of mixotrophic algae has been recorded under the sea ice in the Arctic.

More information: An under-ice bloom of mixotrophic haptophytes in low nutrient and freshwater-influenced Arctic waters.http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-82413-y